A new study by MIT scientists has revealed that simpler, physics based models can sometimes outperform advanced deep learning systems in predicting climate changes, challenging the growing reliance on massive AI models for environmental forecasting.

The research, published in the Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems, shows that while deep-learning methods have become popular in climate science, they are not always the best choice. In fact, traditional linear pattern scaling (LPS) models proved more accurate than deep-learning models for forecasting regional surface temperatures, despite their simplicity.

Researchers found that the natural variability of climate data such as irregular shifts in weather patterns and long-term oscillations like El Niño and La Niña often confuses AI systems, leading to misleading results. In some cases, benchmarking methods used to test machine-learning models exaggerated their performance, making them seem more effective than they actually were.

To address this, the team developed a more robust evaluation method. Using this improved benchmark, they discovered that deep-learning models perform slightly better for local rainfall predictions, while LPS remains superior for temperature estimates.

“These findings are a cautionary tale,” said senior author Noelle Selin, professor at MIT’s Institute for Data, Systems, and Society (IDSS). “It may be tempting to use the biggest AI model available, but sometimes the most useful solution is the simpler one, especially when grounded in physical science.”

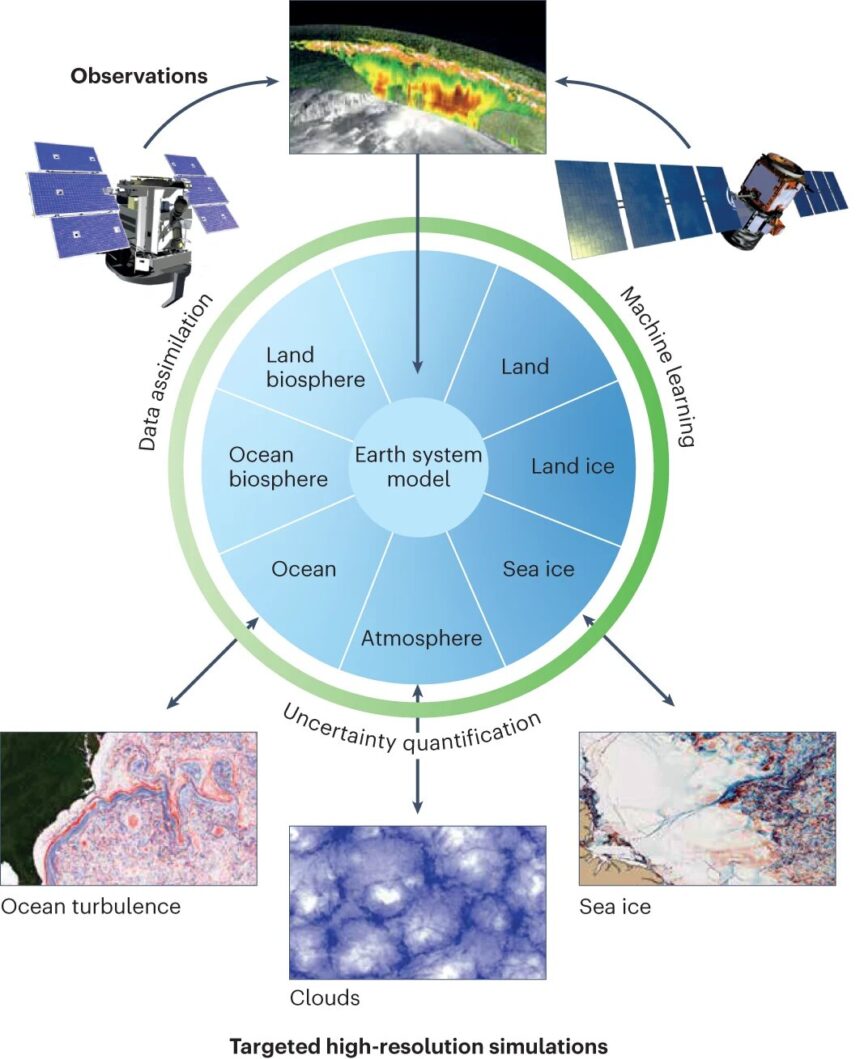

The research highlights the importance of choosing the right tool for the right climate challenge. While climate emulators faster, simplified versions of state of the art climate models are crucial for policymakers, accuracy is key. An emulator that misjudges local climate impacts could mislead decision-making on issues like greenhouse gas regulations.

Lead author Björn Lütjens, now at IBM Research, noted, “Large AI methods are appealing, but before we use them, we need to test whether existing approaches already provide better answers.”

The study also emphasizes the need for better benchmarking tools to fairly evaluate climate prediction models. With improved testing methods, scientists could unlock AI’s full potential in tackling complex challenges such as extreme precipitation, drought impacts, or the role of aerosols.

Ultimately, the researchers argue that climate science requires a balance between innovative machine learning and proven physical models. Their findings call for careful consideration before deploying large AI systems, ensuring policymakers base climate decisions on the most reliable predictions available.

This work is part of MIT’s Bringing Computation to the Climate Challenge project and is supported by Schmidt Sciences, LLC.